|

|

|

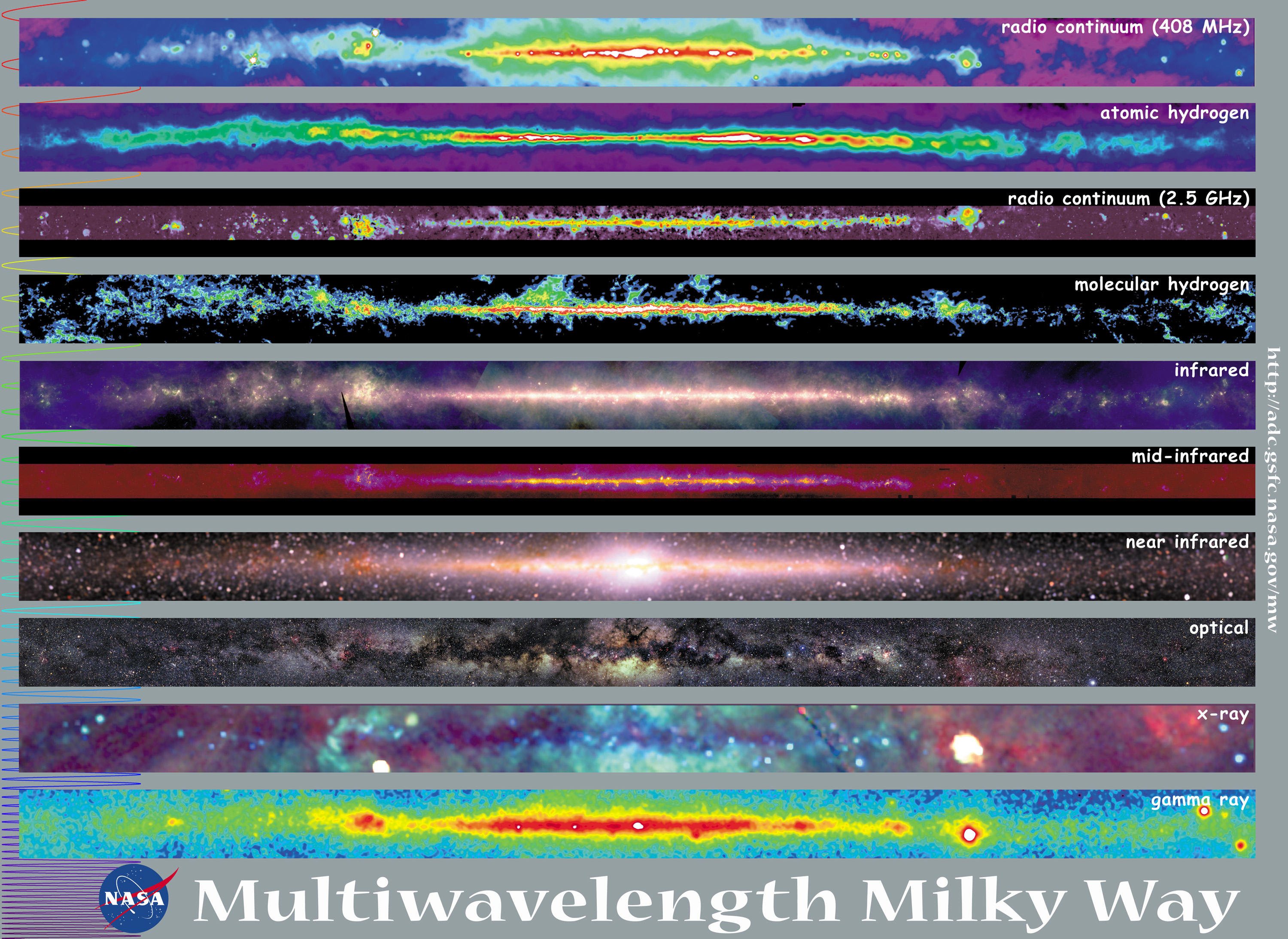

Most of what we know about the universe comes from information that is carried to us by light, i.e. electromagnetic waves, often called electromagnetic radiation because it has electric and magnetic properties. Visible light, coming to our eyes as colors ranging from deep red to deep violet, is only a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum. In recent years. the remaining, “non-visual” ranges - radio waves, microwaves, infrared and ultraviolet rays, x-rays and gamma rays - have been harnessed by scientists in increasingly sophisticated ways to further explore the world around us and “what’s out there.”

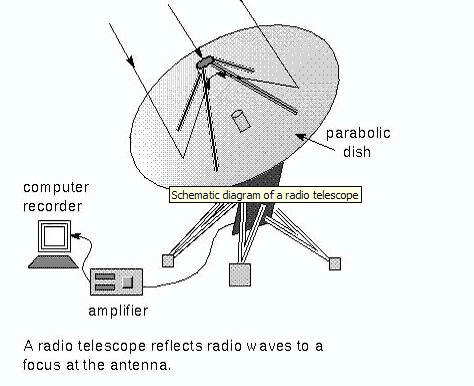

While radio

waves are low in frequency, they have the longest wavelength of

any of the forms of light, so they aren’t scattered by the earth’s

atmosphere before they can be picked up by radio telescopes.

In contrast to "ordinary" telescopes that produce visible

light images, these telescopes detect radio waves emitted by objects

in space and translate those waves into information that, along

with optical telescopes, further our understanding of the universe.

All objects emit radio waves, some stronger than others. A radio telescope "tunes in" to these signals and listens just as does the AM radio in your car - but instead of hearing music, you hear a hiss that, translated by computer, reveals the size, shape, location, distance and intensity of the source.

Our

3.1 meter

Mike Hayden, Director of infrastructure and Operations at Gettysburg College and Program Manager for our 21-cm radio telescope, instigated the not-easy and rather time-consuming project of purchasing it, putting it together, and running it, with the help of volunteers Dick Cooper, '65, Manager for the Physics Department's Project CLEA, Physics electronics technician Gary Hummer, physics major Justin Pryzby,'04, Gettysburg High School student Daniel Rice, and amateur astronomer George Yurick. Cloudy

days mean nothing to a radio telescope, and there are many interesting

things, from the simple to the complex, that faculty, students,

and attendees of Project CLEA's

summer workshops can learn with

it. Combining technologies of microwave engineering and digital

computing, it involves us in astronomy, physics, digital signal

processing, software development, and analysis.

Back to Observatory, Physics Department...or on to pictures and data |